As seen in Khabar Magazine January 2014 print issue

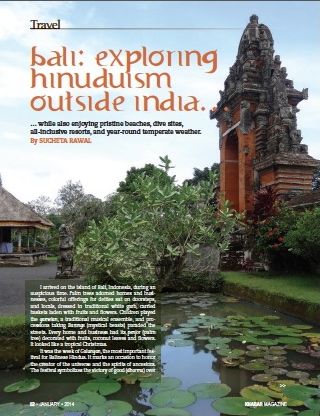

Bali: exploring hinuduism outside India while also enjoying pristine beaches, dive sites, all-inclusive resorts, and year-round temperate weather.

I arrived on the island of Bali, Indonesia, during an auspicious time. Palm trees adorned homes and businesses, colorful offerings for deities sat on doorsteps, and locals, dressed in traditional white garb, carried baskets laden with fruits and flowers. Children played the gamelan, a traditional musical ensemble, and processions taking Barongs (mystical beasts) paraded the streets. Every home and business had its penjor (palm tree) decorated with fruits, coconut leaves and flowers. It looked like a tropical Christmas.

It was the week of Galungan, the most important festival for Balinese Hindus. It marks an occasion to honor the creator of the universe and the spirits of ancestors. The festival symbolizes the victory of good (dharma) over evil (adharma), and encourages the Balinese to show their gratitude to the creator and the saints from their ancestry. During this holy period, people cook special cakes (known as jaja) in pots of clay, visit family members, and pray at multiple temples.

The Tanah Lot—the most photographed temple in Bali

It is easy to get lost in the architectural beauty of over fifty thousand temples in a mere 2,232 square miles. I questioned my host, Sri Ekayanti Ni Wayan (who goes by Eka), why Balinese people felt a need for so many temples. “It is mandatory to have a temple at one’s home, a family temple and a village temple. Every village also has three temples, each dedicated to the Gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. Therefore, a Balinese person prays at least three temples daily,” she informed me. They would also visit some of the larger temples during festivals or special occasions.

Eka invited me to her family temple, in the village of Sukawati. The family members, consisting of about 100 people, gathered in the evening to celebrate the temple’s anniversary, which is held every six months. Women are required to cover their legs before entering the tem¬ple; therefore sarongs (similar to the Indian lungi) are available at most public temples. There is a technique for properly tying a sarong with a sash, which Eka had to demonstrate for me, even though I have draped myself in a sari many times before. I was taken through the common grounds of the temple into an inside chamber, where we sat on the floor. Some of the women blessed me with flowers and incense, sprinkled holy water and dotted my forehead with uncooked rice. It was not clear which God we were praying to, as the Balinese Hindus do not practice idol worship. (Different colors identify each God: red for Brahma, black for Vishnu and white for Shiva.) Then we gathered to watch children from the community perform traditional music and dance.

A procession of temple offerings during Galungan

The Balinese temples (called pura) are different from an Indian Hindu temple. An outdoor complex of small buildings leads into a series of gates to reach the interiors of the temples. The Balinese people are associated to a particular temple by virtue of descent, residence, or some mystical revelation of affiliation. Some temples are associated with the family house compound (also called banjar in Bali), others are associated with rice fields, and still others with key geographic sites.

While visitors cannot enter most family temples, there are some well-known temples in Bali that are also major tourist attractions. During my stay in Ubud, the central region of Bali that is nestled among rice paddies and volcanic hills, I visited Pura Tirta Empul. Dating back to 926 AD, the temple has a pool known to have healing powers. Locals take a dip in the sacred waters hoping to purify themselves.

Taman Ayun (“beautiful garden”) is a family temple belonging to the Raja of Mengwi and built in 1634 AD. This is one of the most beautiful temples in Bali, characterized by towering Balinese pagodas (known as Meru) made of odd-numbered black thatched roofs. The temple complex is surrounded by gardens that are packed with locals picnicking with families over the weekends.

My favorite of all was Tanah Lot, rightfully named one of the most photographed temples in Bali. It is lo¬cated on a cliff jutting out into the sea, surrounded by black sand and surfing waves, and makes for a picturesque view especially during sunset. During high tides, the rock looks like a large boat at sea.

The profusion of temples in Bali is not surprising considering almost 85 percent of Bali’s population fol¬lows Hinduism, which is said to have come to Indonesia from India in the fifth century. By the eleventh century, Java and Sumatra were seeing an increase in the popularity of Buddhism, which was eventually replaced by Islam. However, due to geographical barriers, the island of Bali was the only part of Indonesia that remained Hindu, while the rest of the country experienced Muslim conversions.

There are similarities between Balinese Hinduism and that found in India. It follows the belief of rebirth, karma and nirvana, divides the cosmos into three layers (heaven, human and hell), and is deeply embodied in rituals celebrating birth, marriage, death, and everything in between. Balinese Hinduism is deeply interwo¬ven with art and ritual, which is reflected in the various festivals celebrated throughout the year.

A typical meal of whole grilled fish, steamed rice, and sambal.

Hindu mythological characters and scriptures also inspire Balinese music and dance. Traditional dances depict episodes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, and are taught to children early on. At the Sukawati temple celebrations, Eka’s nine-year old daughter and her classmates performed temple dances dressed in one-shoulder gold wrap and peacock-shaped headwear, gesturing with captivating eye and facial expressions. A dance-drama played out the battle between the mythical characters Rangda (a witch representing adharma) and Barong, the protective predator (representing dharma), in which performers fell into a trance and attempt¬ed to stab themselves with sharp knives.

Dance schools around the island run by genera¬tions of artistes hold classes for adults and children who want to practice traditional Balinese dances. For spectators, many local restaurants, temples, and cul¬tural centers offer Balinese folklore performances for a cover charge of about $8-10.

In recent years, Bali has become a major attraction for travelers seeking spirituality through yoga, meditation, healing, and vegetarianism. Many yoga schools, retreat centers, and spas offer a chance to develop spiritual and physical being. Styles of yoga and movement taught in Bali include Hatha, Vinyasa Flow, Yin, Laughter, Power, Anusara, Ashtanga, Silat, Capoeira, Poi, Qi Gong, and Juggling. The annual Bali Spirit Festival gathers world-renowned musicians, yogis, and dancers to illustrate the Balinese Hindu concept of Tri Hita Karana: living in harmony with our spiritual, social, and natural environments. Yoga teacher training, cleansing detox, and meditation retreats are offered to international vis¬itors before and after the festival. Balinese Hindus, unlike a large percentage of other Hindus, are not vegetarian. They eat chicken, fish, and pork. However, there are many juice bars, vegan restaurants, and vegetarian restaurants serving international cuisine in Bali. It is common to overhear tourists from different parts of the world discussing afterlife and spirituality over a lunch of tempeh curry and herbal tea at a café in Ubud.

Yoga Barn

Coming back to the festival of Galungan, I am lost in the sights and sounds that make up the spectacle of the Dance of the Barong, performed through the streets of Bali during this time. Like in a dragon dance, two people wear a costume as they lead a crowd of followers through the village with much clanging to announce their approach. The Barong, even though frightening to look at because of its fiery eyes and animalistic hair, is meant to restore the balance of good and evil at a Balinese home.

The tenth day, Kuningan, marks the end of Galungan, and is believed to be the day when the spirits ascend back to heaven. On this day, Balinese families get together, make offerings, and pray. Then they have a feast where traditional Balinese dishes such as lawar (a spicy pork and coconut sauce dish) and satay (chicken tenders grilled on bamboo sticks) are served.

While most Western tourists visit Bali for its pristine beaches, dive sites, all-inclusive resorts, and year-round temperate weather, the more unforgettable attractions remain the region’s colorful art, vivid dances, rich culture, and Hindu festivals. Hindu customs in Bali have been preserved over thousands of years and form an integral part of everyday life.

| Most popular temples in Bali Pura Besakih – Also known as Mother Temple or the Temple of Spiritual Happiness, this is the most import¬ant temple for Balinese ceremonies.Pura Tanah Lot – The most photographed temple in Bali sits atop a high rock with a backdrop of foamy white waves and black sand.

Pura Luhur Uluwatu – Perched on cliffs against a surf break against the sea, it is spectacular to visit during sunset. Pura Tirta Empul – Fitted with two holy springs, it is a popular place for the Balinese to bathe for spiritual cleansing. Pura Ulun Danu Bratan – Situated in beautiful surround¬ings, the temple juts out onto a lake. Goa Lawah Temple – The 1,000-year-old-cave temple swarms with bats and is one of the most unique temples in the world. Taman Ayun Temple in Mengwi – Surrounded by beautiful gardens, it is a good place to see the famous Balinese pagodas. Pura Goa Giri Putri – Nestled inside a mountain cave, the dwelling place of God symbolizes the power of a woman. |